Java remains one of the most dominant forces in the software industry, powering everything from Android mobile applications to massive enterprise microservices on the cloud. While many developers begin their journey with a simple “Hello World,” true mastery of Java Development requires a profound understanding of what happens beneath the surface. The architecture of Java is a sophisticated orchestration of compilation, class loading, memory management, and just-in-time execution that allows it to maintain its famous “Write Once, Run Anywhere” promise.

Understanding Java Architecture is not merely academic; it is essential for writing high-performance code, troubleshooting memory leaks, and optimizing Java Backend systems. Whether you are working with Java 17, the latest Java 21, or maintaining legacy systems, the fundamental principles of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) remain the bedrock of the ecosystem. In this comprehensive guide, we will dissect the internal pipeline of Java execution, explore the memory model, and demonstrate how to leverage modern architectural patterns in your code.

The Core Components: JDK, JRE, and JVM

Before diving into the internal mechanics, it is crucial to distinguish between the three core pillars of the Java environment. This is often the first stumbling block for beginners in Java Programming.

- JDK (Java Development Kit): This is the full toolbox for developers. It includes the JRE, the compiler (

javac), the archiver (jar), and documentation generators. If you are building Java Spring applications or writing Java Basics, you need the JDK. - JRE (Java Runtime Environment): This is the implementation required to run Java applications. It contains the JVM and the core libraries (like

java.lang,java.util). - JVM (Java Virtual Machine): The heart of the architecture. It is an abstract computing machine that enables a computer to run a Java program. The JVM handles Class Loading, verification, memory allocation, and execution.

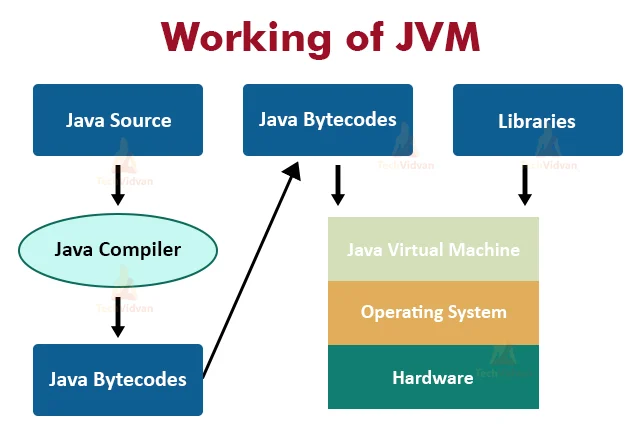

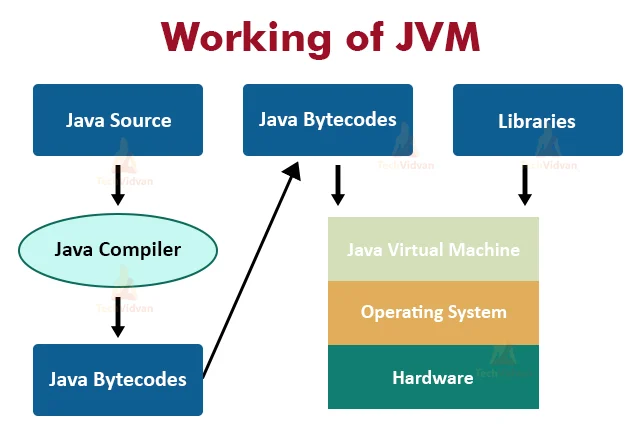

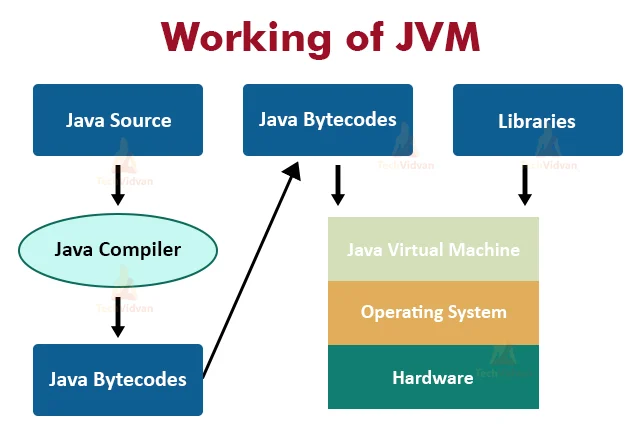

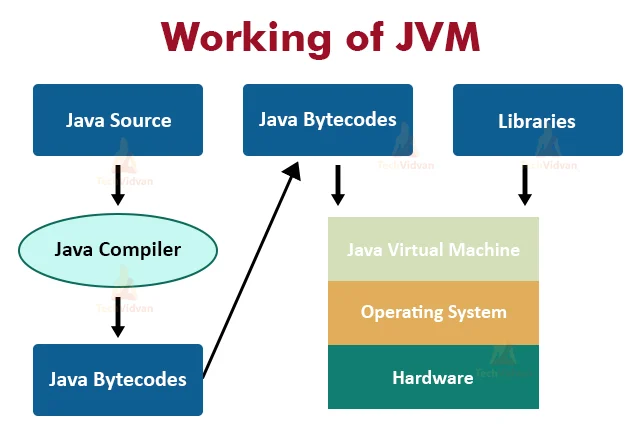

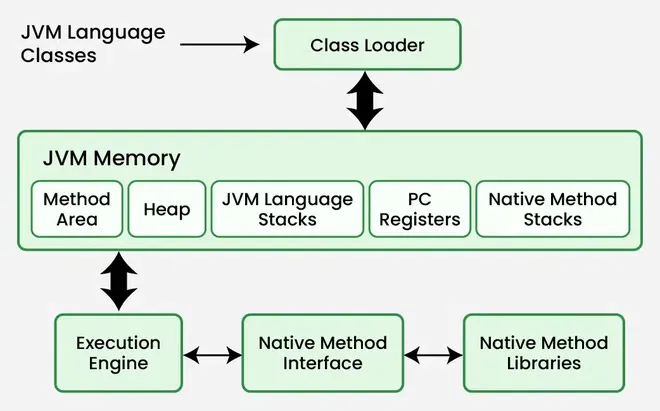

Section 1: The JVM Execution Pipeline

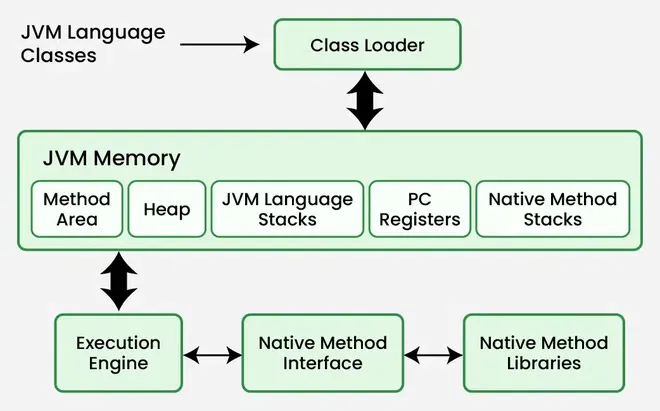

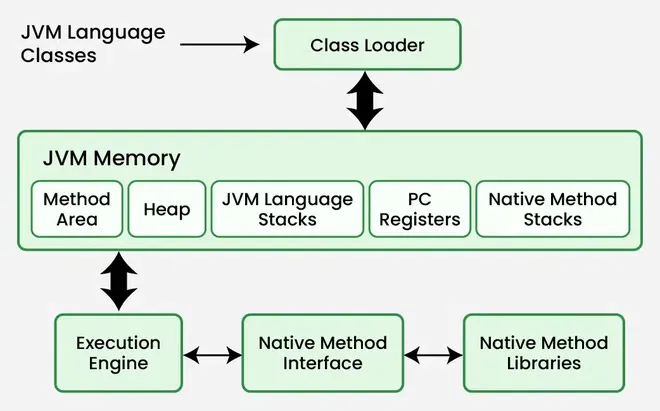

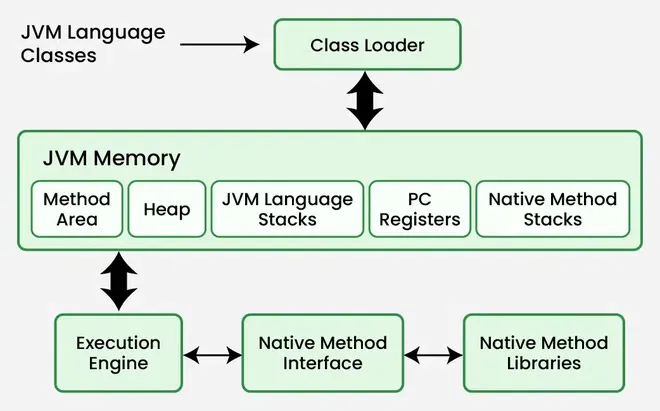

When you compile Java source code (.java), it is transformed into bytecode (.class). This bytecode is platform-agnostic. The magic happens when the JVM loads this bytecode. The execution pipeline consists of three main subsystems: the ClassLoader Subsystem, the Runtime Data Areas, and the Execution Engine.

1. The ClassLoader Subsystem

Java uses a dynamic class loading mechanism. Classes are not loaded into memory all at once; they are loaded on demand. The subsystem performs three distinct phases:

- Loading: The Bootstrap ClassLoader loads core libraries (

rt.jar), the Extension ClassLoader loads specific extensions, and the Application ClassLoader loads your code found in the classpath. - Linking: This involves Verification (ensuring bytecode is valid and safe), Preparation (allocating memory for static variables), and Resolution (replacing symbolic references with direct references).

- Initialization: Static blocks are executed, and static variables are assigned their initial values.

To understand how we structure code for the JVM, let’s look at a practical example using Interfaces and Polymorphism, which relies heavily on the JVM’s ability to resolve methods at runtime.

package com.java.architecture.core;

// Defining a contract for our payment system

interface PaymentProcessor {

void processPayment(double amount);

boolean validateCurrency(String currency);

}

// Concrete implementation for Credit Card

class CreditCardProcessor implements PaymentProcessor {

@Override

public void processPayment(double amount) {

System.out.println("Processing credit card charge: $" + amount);

// Logic to connect to banking gateway

}

@Override

public boolean validateCurrency(String currency) {

return "USD".equals(currency) || "EUR".equals(currency);

}

}

// Concrete implementation for Crypto

class CryptoProcessor implements PaymentProcessor {

@Override

public void processPayment(double amount) {

System.out.println("Processing crypto transaction block: " + amount);

}

@Override

public boolean validateCurrency(String currency) {

return "BTC".equals(currency) || "ETH".equals(currency);

}

}

public class PaymentService {

// The JVM resolves the specific implementation at runtime

public static void executeTransaction(PaymentProcessor processor, double amount) {

if (processor.validateCurrency("USD")) {

processor.processPayment(amount);

} else {

System.out.println("Currency not supported by this processor.");

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Class loading happens here for CreditCardProcessor

PaymentProcessor card = new CreditCardProcessor();

// Class loading happens here for CryptoProcessor

PaymentProcessor crypto = new CryptoProcessor();

executeTransaction(card, 150.00);

executeTransaction(crypto, 0.05);

}

}Section 2: Runtime Data Areas and Memory Management

Once the class is loaded, the JVM allocates memory. Understanding the distinction between the Stack and the Heap is vital for avoiding StackOverflowError and OutOfMemoryError, common issues in Java Enterprise applications.

The Stack vs. The Heap

The Stack creates a frame for every method invocation. It stores local variables, partial results, and method return values. It is thread-safe as each thread has its own stack. The Heap is the runtime data area from which memory for all class instances and arrays is allocated. It is shared among all threads, making it the subject of Garbage Collection.

Modern Java versions, including Java 17 and Java 21, use sophisticated Garbage Collectors like G1GC (Garbage First) and ZGC to manage the heap efficiently. The GC process involves identifying “live” objects and sweeping away “dead” objects to free up memory.

Here is an example demonstrating how objects are stored in the Heap while references and primitives live on the Stack. This is crucial for Java Performance optimization.

package com.java.architecture.memory;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class MemoryArchitectureDemo {

// Stored in the Metaspace (Method Area)

private static final int MAX_CACHE_SIZE = 1000;

public static void main(String[] args) {

// 'dataProcessor' reference is on the Stack

// The DataProcessor object is on the Heap

DataProcessor dataProcessor = new DataProcessor();

// Primitive 'count' is stored directly on the Stack

int count = 5000;

dataProcessor.processData(count);

}

}

class DataProcessor {

// Instance variables live on the Heap inside the object

private List cache = new ArrayList<>();

public void processData(int volume) {

// 'volume' is a local variable on the Stack Frame for this method

for (int i = 0; i < volume; i++) {

// String objects are created on the Heap

// References are added to the list

String data = "Data-Packet-" + i;

// Potential Memory Leak: If we never clear this cache

cache.add(data);

}

System.out.println("Processed " + cache.size() + " items.");

}

} Section 3: Execution Engine and Advanced Techniques

The Execution Engine is where the bytecode is actually run. It uses an Interpreter to read bytecode line by line, but for performance, it employs the JIT (Just-In-Time) Compiler. The JIT compiler identifies "hot spots" (frequently called methods) and compiles them into native machine code for direct execution by the CPU. This is why Java Optimization often focuses on "warming up" the JVM.

Modern Java: Streams and Functional Programming

Since Java 8, the architecture has evolved to support functional programming paradigms. Java Streams and Java Lambda expressions allow developers to process collections of data declaratively. Under the hood, streams can leverage multi-core architectures via the Fork/Join framework, enhancing Java Scalability.

Let's look at a modern implementation using Streams, Records (introduced in Java 14/16), and functional interfaces. This style is prevalent in Java Microservices and Spring Boot applications.

package com.java.architecture.advanced;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

// Java Record - Immutable data carrier (Java 16+)

record Transaction(String id, String type, double amount, String status) {}

public class StreamArchitecture {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List transactions = List.of(

new Transaction("TX1", "DEBIT", 100.00, "COMPLETED"),

new Transaction("TX2", "CREDIT", 500.00, "COMPLETED"),

new Transaction("TX3", "DEBIT", 20.00, "FAILED"),

new Transaction("TX4", "DEBIT", 100.00, "COMPLETED"),

new Transaction("TX5", "CREDIT", 1200.00, "PENDING")

);

// Functional Pipeline: Filter -> Group -> Sum

// This leverages the Stream API architecture

Map totalByStatus = transactions.stream()

.filter(t -> t.amount() > 50.00) // Filter small transactions

.collect(Collectors.groupingBy(

Transaction::status,

Collectors.summingDouble(Transaction::amount)

));

System.out.println("Transaction Totals by Status: " + totalByStatus);

// Parallel Stream for high-volume data processing

// Uses the common ForkJoinPool internally

double totalProcessedVolume = transactions.parallelStream()

.filter(t -> "COMPLETED".equals(t.status()))

.mapToDouble(Transaction::amount)

.sum();

System.out.println("Total Processed Volume: " + totalProcessedVolume);

}

} Section 4: Enterprise Architecture and Best Practices

Moving from the JVM internals to application architecture, modern Java Web Development relies heavily on frameworks like Spring Boot and Jakarta EE. These frameworks abstract much of the lower-level complexity, providing containers for dependency injection and lifecycle management.

Concurrency and Asynchronous Processing

Java Concurrency has always been a strong suit. With the introduction of CompletableFuture and, more recently, Virtual Threads (Project Loom) in Java 21, handling high-throughput I/O operations in Java Cloud environments (like AWS Java or Azure Java) has become significantly more efficient.

Below is an example of asynchronous architecture using CompletableFuture to simulate fetching data from multiple external APIs (a common pattern in Java Microservices).

package com.java.architecture.async;

import java.util.concurrent.CompletableFuture;

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutionException;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class AsyncServiceDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

System.out.println("Starting Async Orchestration...");

// Simulate fetching User Profile (Async)

CompletableFuture userFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

simulateNetworkDelay(1);

return "User: John Doe";

});

// Simulate fetching User Orders (Async)

CompletableFuture ordersFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

simulateNetworkDelay(2);

return "Orders: [Order#123, Order#124]";

});

// Simulate fetching User Analytics (Async)

CompletableFuture analyticsFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

simulateNetworkDelay(1);

return "Analytics: Active";

});

// Combine all independent futures

CompletableFuture allFutures = CompletableFuture.allOf(

userFuture, ordersFuture, analyticsFuture

);

// When all are done, process the result

allFutures.thenRun(() -> {

try {

String user = userFuture.get();

String orders = ordersFuture.get();

String analytics = analyticsFuture.get();

System.out.println("Aggregated Response:");

System.out.println(user);

System.out.println(orders);

System.out.println(analytics);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}).get(); // Blocking here just for the main method demonstration

}

private static void simulateNetworkDelay(int seconds) {

try {

TimeUnit.SECONDS.sleep(seconds);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

} Best Practices and Optimization Strategies

To ensure your Java architecture remains robust and scalable, adhere to the following best practices:

1. JVM Tuning and Monitoring

Never rely solely on default settings for production environments. Use JVM Tuning flags to configure heap size (-Xms, -Xmx) and select the appropriate Garbage Collector. Tools like VisualVM and JConsole are essential for monitoring memory consumption and thread activity.

2. Dependency Management and Build Tools

Use Java Maven or Java Gradle to manage dependencies. This ensures that your Java Build Tools handle the classpath complexity, allowing for reproducible builds in CI/CD Java pipelines using Jenkins, GitLab CI, or GitHub Actions.

3. Security First

Java Security is paramount. When building Java REST APIs, integrate OAuth Java and JWT Java libraries for Java Authentication. Ensure dependencies are scanned for vulnerabilities to prevent supply chain attacks.

4. Testing and Clean Code

Adopt Clean Code Java principles. Write unit tests using JUnit and Mockito. Java Testing is not an afterthought; it is an architectural requirement. High test coverage ensures that refactoring does not introduce regressions.

Conclusion

The architecture of Java is a testament to engineering excellence. From the moment the class loader ingests bytecode to the millisecond the JIT compiler optimizes a hot loop into native machine code, the JVM performs a complex ballet of operations to ensure performance and stability. By understanding the distinction between the JDK, JRE, and JVM, mastering the memory model of the Heap and Stack, and utilizing modern concurrency patterns like CompletableFuture and Streams, developers can build systems that are not only functional but truly enterprise-grade.

As the ecosystem evolves with Java 21, GraalVM, and cloud-native technologies like Docker Java and Kubernetes Java, the foundational knowledge of Java architecture becomes even more critical. Whether you are optimizing a legacy monolith or deploying serverless functions on Google Cloud Java, the principles discussed here will serve as your guide to mastering the Java platform.