In the vast ecosystem of Java Development, the definition of “quality” has evolved significantly over the last decade. Historically, developers often equated quality with strict adherence to syntax rules or the clever use of design patterns. However, as modern applications grow into complex Java Microservices and distributed systems, the philosophy of Clean Code Java has shifted. It is no longer just about readability; it is about strategic design, maintainability, and aligning the codebase with the business domain.

Writing clean code in Java 17 or Java 21 requires a mindset that goes beyond the surface level. While formatting and naming conventions remain important, the true challenge lies in structuring logic so that it survives the changing requirements of a Java Enterprise environment. Many teams utilizing Spring Boot or Jakarta EE find themselves trapped in a cycle of wiring “anemic” data structures to bloated service layers, mistakenly believing they are practicing Domain-Driven Design (DDD). True clean code bridges the gap between technical implementation and strategic business intent.

This comprehensive guide explores the depths of writing clean, maintainable, and strategic Java code. We will cover modern syntax features, the importance of rich domain models, functional programming paradigms with Java Streams, and architectural best practices that facilitate Java Testing and deployment. Whether you are working on Android Development or high-scale Java Backend systems, these principles are universal.

The Foundation: Modern Syntax and Expressive Types

The first step toward Clean Code Java is leveraging the language’s modern features to reduce boilerplate and increase expressiveness. Legacy Java codebases are often plagued by verbose classes that obscure the developer’s intent. With the advent of newer JDK versions, we have tools that allow us to write concise, immutable data structures that are thread-safe by default—a crucial factor for Java Concurrency.

Embracing Immutability with Records

In the past, creating a simple Data Transfer Object (DTO) required private fields, getters, setters, equals(), hashCode(), and toString() methods. This noise made it difficult to spot actual business logic. Java Best Practices now recommend using Java Records (introduced in Java 14/16) for immutable data carriers. This not only cleans up the code but also helps with JVM Tuning and Garbage Collection efficiency by encouraging the creation of short-lived, immutable objects.

Consider a scenario in a Java Web Development project where we need to represent a user registration request. A clean approach validates data upon construction and ensures the object remains valid throughout its lifecycle.

package com.cleanarchitecture.domain;

import java.util.Objects;

import java.util.regex.Pattern;

/**

* A clean, immutable representation of a user registration using Java Records.

* This replaces verbose POJOs and ensures data integrity at the constructor level.

*/

public record UserRegistration(String username, String email, String password) {

private static final Pattern EMAIL_PATTERN = Pattern.compile("^[A-Za-z0-9+_.-]+@(.+)$");

// Compact constructor for validation logic

public UserRegistration {

Objects.requireNonNull(username, "Username cannot be null");

Objects.requireNonNull(email, "Email cannot be null");

if (username.isBlank()) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Username cannot be empty");

}

if (!EMAIL_PATTERN.matcher(email).matches()) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Invalid email format");

}

if (password == null || password.length() < 8) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Password must be at least 8 characters");

}

}

// Domain logic can still reside here if it pertains strictly to the data state

public boolean isCorporateEmail() {

return email.endsWith("@company.com");

}

}In the example above, the code is declarative. We don't waste lines on boilerplate. The validation logic is encapsulated, preventing the rest of the system (like the Java REST API layer) from ever dealing with an invalid UserRegistration object. This is a core tenet of Java Security: fail fast and validate inputs early.

Meaningful Naming and Type Safety

Clean code relies heavily on semantics. Variable names like d or list are unacceptable. Furthermore, relying on primitive types for domain concepts (Primitive Obsession) is a common pitfall. Instead of passing a String for a Customer ID, create a strongly typed CustomerId class or record. This prevents bugs where arguments are swapped accidentally and makes the method signatures self-documenting.

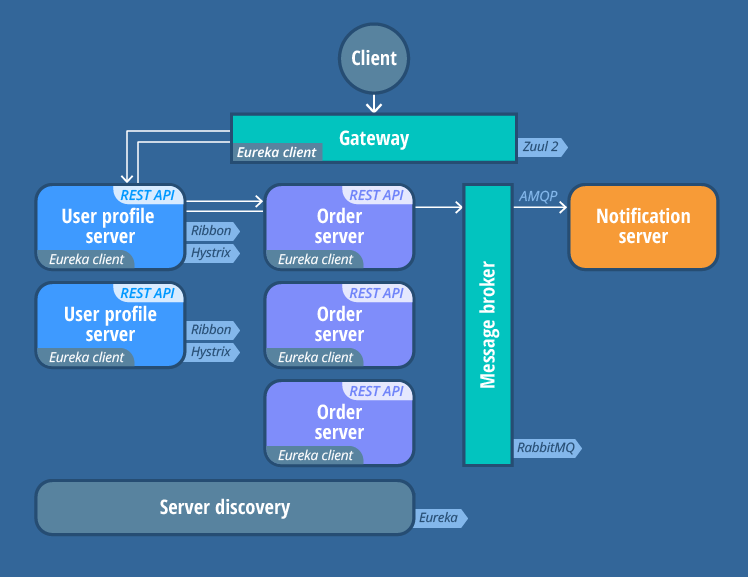

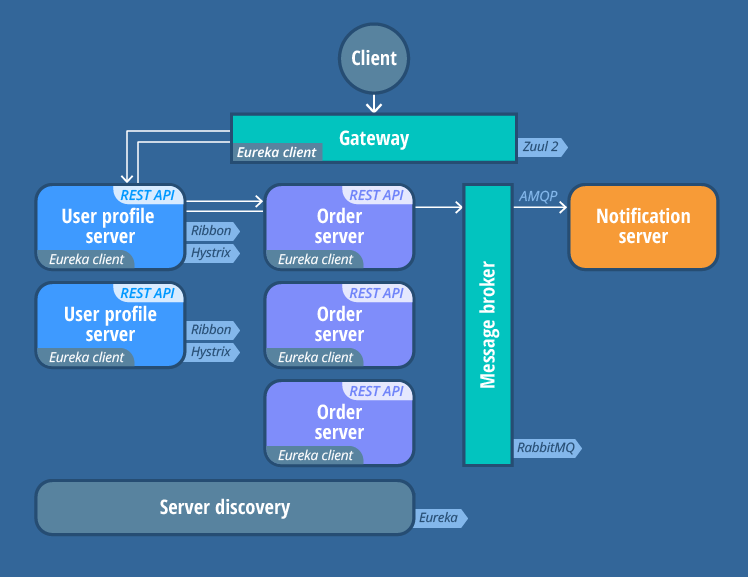

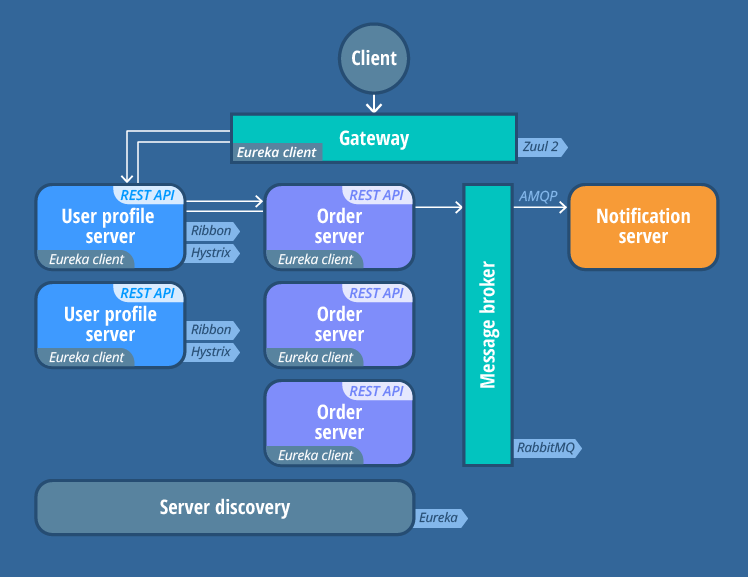

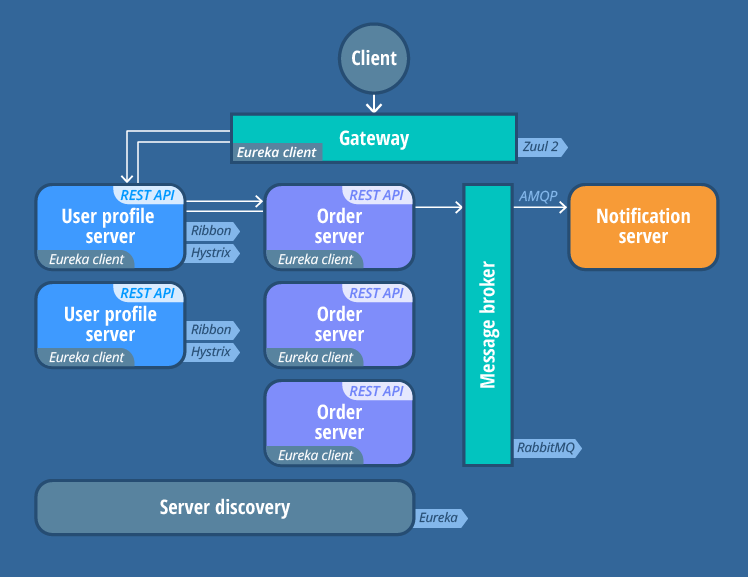

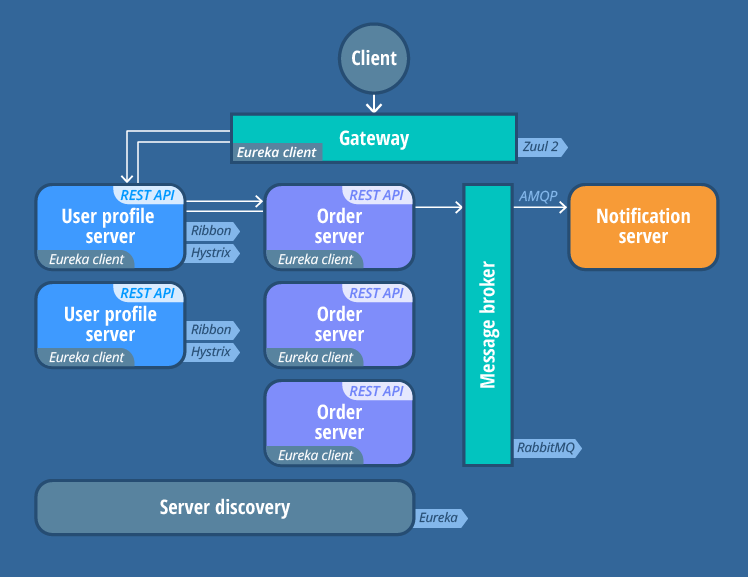

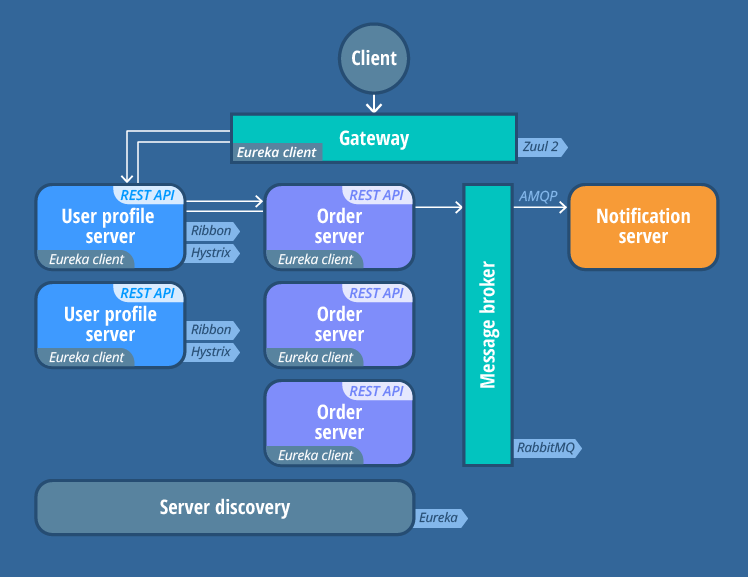

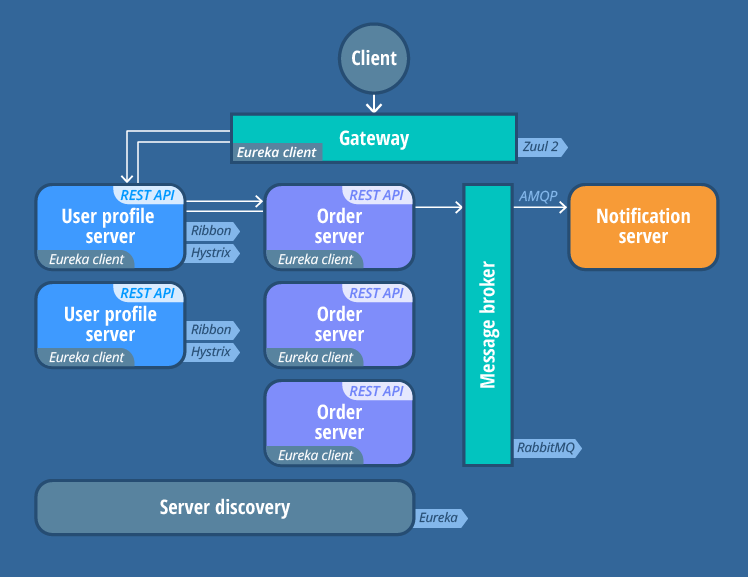

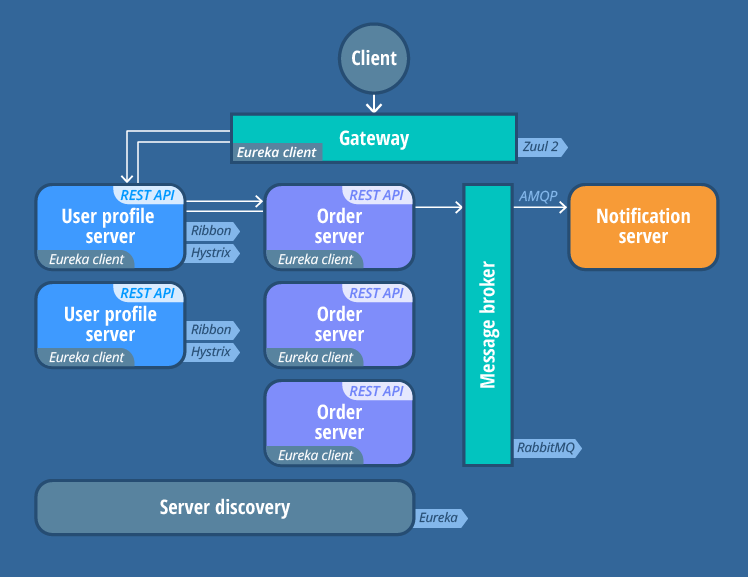

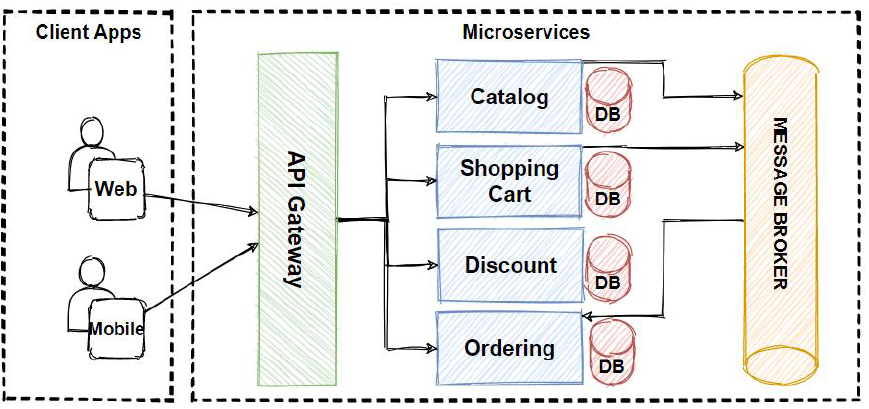

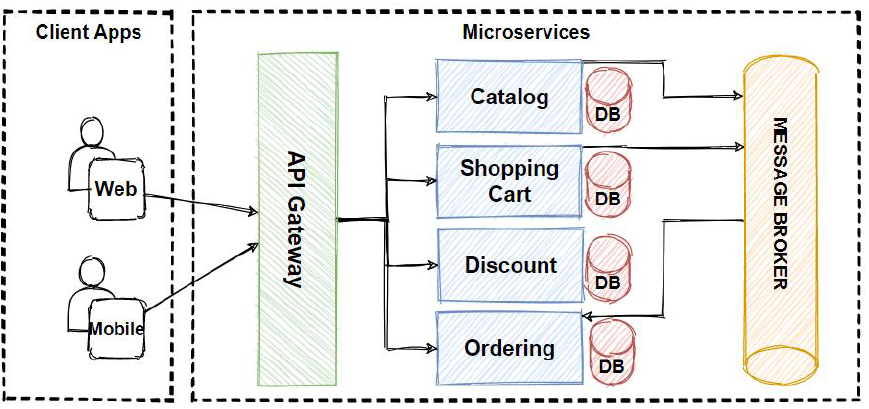

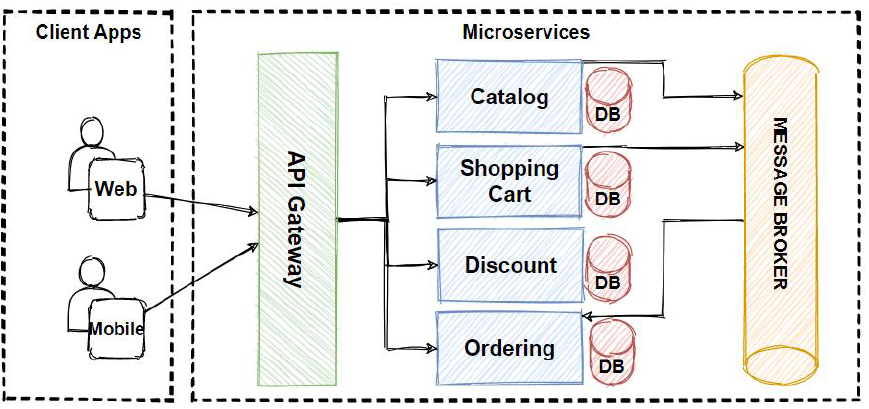

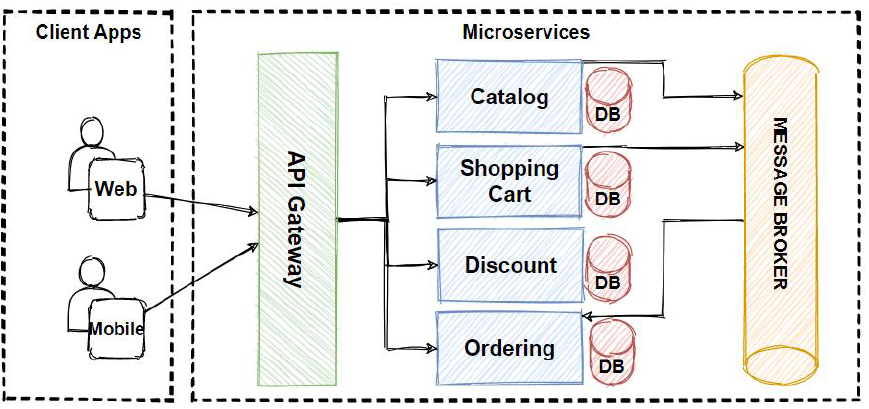

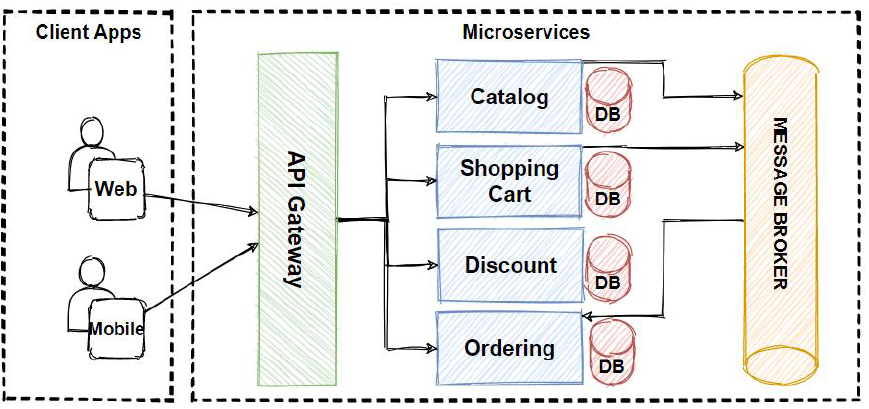

![Microservices architecture diagram - Microservices architecture example [10] | Download Scientific Diagram](https://javacoder.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/inline_f0289909.png)

![Microservices architecture diagram - Microservices architecture example [10] | Download Scientific Diagram](https://javacoder.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/inline_f0289909.png)

![Microservices architecture diagram - Microservices architecture example [10] | Download Scientific Diagram](https://javacoder.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/inline_f0289909.png)

![Microservices architecture diagram - Microservices architecture example [10] | Download Scientific Diagram](https://javacoder.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/inline_f0289909.png)

![Microservices architecture diagram - Microservices architecture example [10] | Download Scientific Diagram](https://javacoder.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/inline_f0289909.png)

Strategic Design: Moving Beyond Anemic Models

One of the most significant failures in modern Java Spring projects is the prevalence of the "Anemic Domain Model." This occurs when developers create entities that are nothing more than bags of getters and setters (often generated by Hibernate or JPA tooling), and push all business logic into "Service" classes. While this separates concerns technically, it fragments business logic, making the code difficult to reason about and harder to refactor.

To achieve Clean Code Java, we must adopt a "Rich Domain Model." This aligns with strategic design principles where the code reflects the business language. Objects should possess both data and the behavior that operates on that data. This is the essence of Object-Oriented Programming: encapsulation.

Implementing Business Logic in Entities

Let's look at an e-commerce example. An anemic approach would have an OrderService calculating the total price. A clean, strategic approach places that logic inside the Order entity itself. This ensures that the state of an Order cannot be mutated into an invalid state, regardless of which service calls it.

package com.cleanarchitecture.domain.model;

import java.math.BigDecimal;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Collections;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.UUID;

public class Order {

private final UUID id;

private final List items;

private OrderStatus status;

private BigDecimal totalAmount;

public Order() {

this.id = UUID.randomUUID();

this.items = new ArrayList<>();

this.status = OrderStatus.DRAFT;

this.totalAmount = BigDecimal.ZERO;

}

// Business Method: Adding an item triggers recalculation

public void addItem(Product product, int quantity) {

if (this.status != OrderStatus.DRAFT) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Cannot add items to a finalized order");

}

if (quantity <= 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Quantity must be positive");

}

OrderItem newItem = new OrderItem(product, quantity);

this.items.add(newItem);

recalculateTotal();

}

// Business Method: Encapsulating state transition

public void confirm() {

if (this.items.isEmpty()) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Cannot confirm an empty order");

}

this.status = OrderStatus.CONFIRMED;

}

private void recalculateTotal() {

this.totalAmount = items.stream()

.map(OrderItem::subtotal)

.reduce(BigDecimal.ZERO, BigDecimal::add);

}

// Expose immutable view of the list to protect internal state

public List getItems() {

return Collections.unmodifiableList(items);

}

public BigDecimal getTotalAmount() {

return totalAmount;

}

} In this example, the Order class protects its invariants. You cannot add an item to a confirmed order. You cannot have a total that doesn't match the sum of items. This reduces the cognitive load on the developer working on the Java Backend because they don't need to hunt through service layers to understand the rules governing an order.

Advanced Techniques: Functional Paradigms and Streams

Java 8 introduced a paradigm shift with Java Streams and Java Lambda expressions. When used correctly, these tools significantly enhance code cleanliness by replacing imperative control flow (nested for-loops and if-statements) with declarative data processing pipelines. This is particularly useful in Java Data Processing tasks.

Refactoring to Declarative Pipelines

Clean code prefers "what to do" over "how to do it." However, developers must be wary of over-engineering streams into unreadable "spaghetti code." A clean stream pipeline should be read from top to bottom like a sentence. Using Java Generics and method references improves readability further.

Below is an example of processing a list of transactions to find high-value targets, converting them to a secure format, and collecting them. This touches on concepts relevant to Java Collections and Java Performance.

package com.cleanarchitecture.service;

import java.math.BigDecimal;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.stream.Collectors;

public class TransactionAnalyzer {

private static final BigDecimal THRESHOLD = new BigDecimal("10000.00");

public Map> groupHighValueTransactionsByCurrency(List transactions) {

if (transactions == null || transactions.isEmpty()) {

return Map.of();

}

return transactions.stream()

// Filter: Keep only successful, high-value transactions

.filter(Transaction::isSuccessful)

.filter(t -> t.getAmount().compareTo(THRESHOLD) > 0)

// Map: Transform domain entity to DTO (Data Transfer Object)

.map(this::toTransactionDto)

// Collect: Group by currency code

.collect(Collectors.groupingBy(TransactionDto::currency));

}

private TransactionDto toTransactionDto(Transaction transaction) {

return new TransactionDto(

transaction.getId(),

transaction.getAmount(),

transaction.getCurrency()

);

}

} This approach eliminates the risk of "Off-by-one" errors common in loops and handles the logic in a functional style. Note the extraction of the mapping logic into a helper method (toTransactionDto). This is a vital technique in Functional Java: keep the lambdas short or use method references.

Handling Asynchrony Cleanly

In modern Java Cloud environments (like AWS Java or Google Cloud Java), operations are often asynchronous. The CompletableFuture API allows for writing non-blocking code that looks synchronous. This is essential for Java Scalability.

public CompletableFuture processOrderAsync(Order order) {

return CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> inventoryService.reserveStock(order))

.thenCompose(stockReserved -> {

if (stockReserved) {

return paymentService.processPayment(order);

} else {

throw new OrderProcessingException("Insufficient stock");

}

})

.thenApply(paymentResult -> new OrderConfirmation(order.getId(), "SUCCESS"))

.exceptionally(ex -> {

logger.error("Order processing failed", ex);

return new OrderConfirmation(order.getId(), "FAILED");

});

} Best Practices: Architecture, Testing, and Optimization

Writing clean code inside a method is futile if the overall Java Architecture is messy. Clean Code scales up to Clean Architecture (often Hexagonal or Onion Architecture). This separation of concerns is critical for Java DevOps pipelines and CI/CD Java processes, as it allows for isolated testing.

Dependency Inversion and Interfaces

To ensure your code is testable and loosely coupled, rely on abstractions. Do not glue your business logic directly to infrastructure concerns like JDBC, Java Database connections, or external APIs. Define interfaces for what you need, and implement them in the infrastructure layer.

// The "Port" (Interface) lives in the Domain layer

public interface CustomerRepository {

Optional findById(CustomerId id);

void save(Customer customer);

}

// The "Adapter" (Implementation) lives in the Infrastructure layer

@Repository

public class JpaCustomerRepository implements CustomerRepository {

private final SpringJpaCustomerRepo springRepo;

public JpaCustomerRepository(SpringJpaCustomerRepo springRepo) {

this.springRepo = springRepo;

}

@Override

public Optional findById(CustomerId id) {

return springRepo.findById(id.getValue()).map(CustomerMapper::toDomain);

}

@Override

public void save(Customer customer) {

springRepo.save(CustomerMapper.toEntity(customer));

}

} This structure allows you to write unit tests for your business logic using Mockito or JUnit without needing to spin up a database or a Docker Java container. It creates a boundary that protects your core logic from changes in frameworks or libraries.

Optimization and Pitfalls

While abstraction is good, over-abstraction is a violation of clean code. Avoid creating interfaces that only have one implementation (unless required for mocking). Additionally, be mindful of Java Performance. Excessive use of wrappers and functional streams in extremely hot paths (loops running millions of times) can create memory pressure. Profiling tools should be part of your Java Build Tools (Maven/Gradle) workflow to ensure clean code remains performant code.

Finally, consider Java Exceptions. Clean code should not use exceptions for flow control. Define custom, unchecked exceptions for domain errors (like InsufficientFundsException) and handle them globally in a REST controller advice or a boundary layer, keeping the core logic clean of try-catch blocks.

Conclusion

Mastering Clean Code Java is a continuous journey that extends far beyond memorizing syntax. It involves a strategic shift towards Rich Domain Models, embracing the immutability offered by modern Java versions, and utilizing functional programming to clarify intent. It requires the discipline to refactor relentlessly and the foresight to architect systems that decouple business rules from infrastructure details.

As the Java ecosystem continues to expand with Kotlin vs Java debates, cloud-native solutions on Kubernetes Java, and advanced Java Cryptography requirements, the principles of clean code remain the stable foundation. By focusing on the "why" behind the code—the business strategy—developers can build systems that are not only bug-free but are also adaptable assets to the organization. Start by reviewing your current aggregates, refactoring anemic services, and ensuring your code tells the story of your domain.