If I had a dollar for every time someone told me Jakarta EE was dead, I could probably retire to a nice beach house and stop debugging race conditions. Yet, here I am in late 2025, looking at my project backlog, and what do I see? A massive amount of infrastructure still relying heavily on the Jakarta EE specifications.

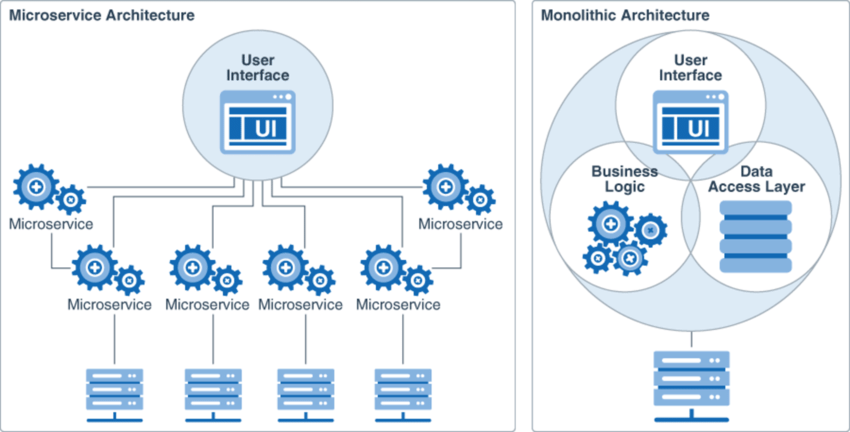

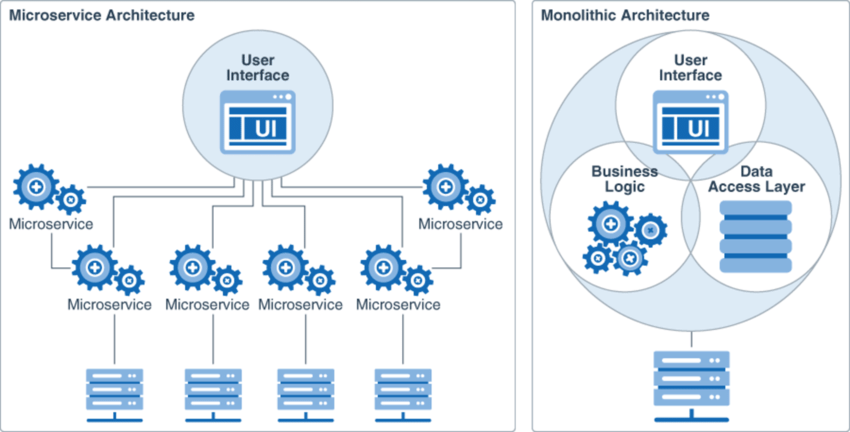

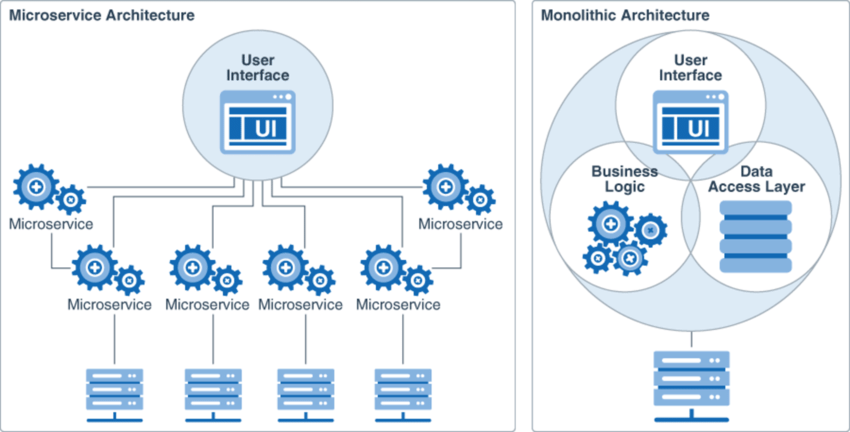

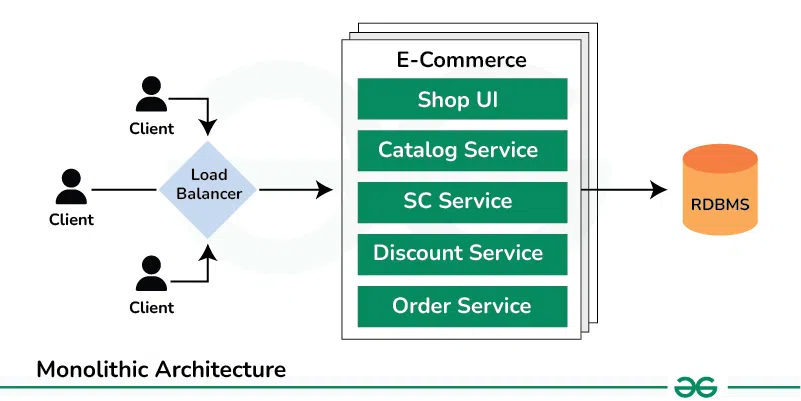

There is a strange obsession in our industry with the “new.” We chase frameworks that promise to solve all our problems, only to realize three years later that we just traded one set of XML configuration files for a complex graph of annotations and YAML hell. I admit, I’ve been part of that cycle. I’ve rewritten perfectly good monoliths into microservices just to put “distributed tracing” on my resume.

But lately, I’ve come to a realization that feels almost rebellious: I actually like Jakarta EE. Not the heavy, XML-laden J2EE of the early 2000s, but the lean, standard-focused ecosystem we have today. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t get the viral blog posts that the latest JavaScript meta-framework gets. But it works, and in 2025, stability is the feature I value most.

The “Zombie” That Runs the Economy

I consult for a lot of mid-to-large enterprises, and the pattern is always the same. Management wants to “modernize.” They bring in consultants who suggest ripping out the “legacy” Jakarta EE applications and replacing them with whatever the flavor of the month is. Six months later, the project is over budget, the new system handles half the throughput of the old one, and they call me in to fix it.

The reality is that Jakarta EE isn’t just surviving; it has effectively become the invisible standard for Java Backend development. Even if you think you aren’t using it, you probably are. If you are writing Spring Boot applications, you are using the Servlet API (likely Jakarta Servlet 6.0 or higher by now), Jakarta Persistence (JPA), and Jakarta Bean Validation. The namespace shift from javax.* to jakarta.* that caused us all headaches a few years ago is now a distant memory, and the ecosystem has settled.

I find that understanding the core specifications makes me a significantly better developer, regardless of the framework I use. When I know how the Java Database connectivity works via JPA directly, I understand why my Hibernate queries are slow, rather than just blaming the framework.

Jakarta EE 11 and Java 21: A Solid Baseline

Since the release of Jakarta EE 11, I’ve been pushing my clients to upgrade their baselines. The biggest win here isn’t some new API, but the alignment with Java 21. We finally have a standard enterprise profile that assumes modern Java features are present.

I remember the pain of trying to use older EE versions with newer Java syntax. It felt like fighting the compiler. Now, using Java Records as Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) in Jakarta REST (formerly JAX-RS) resources feels native. The removal of the Security Manager—which was deprecated in Java for ages—finally happened in the EE specs, cleaning up a lot of the internal complexity that application servers used to carry around.

Here is a snippet of how I write a typical REST controller these days. Notice how clean it is. No getters, no setters, just records and standard annotations.

package com.example.api;

import jakarta.inject.Inject;

import jakarta.ws.rs.*;

import jakarta.ws.rs.core.MediaType;

import jakarta.ws.rs.core.Response;

import java.util.List;

// Java 21 Records make DTOs trivial

public record UserRequest(String username, String email) {}

public record UserResponse(Long id, String username, String status) {}

@Path("/users")

@Produces(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

@Consumes(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON)

public class UserResource {

@Inject

UserService userService;

@POST

public Response createUser(UserRequest request) {

// Validation logic here...

var user = userService.register(request.username(), request.email());

return Response.status(Response.Status.CREATED)

.entity(new UserResponse(user.getId(), user.getUsername(), "ACTIVE"))

.build();

}

@GET

@Path("/{id}")

public UserResponse getUser(@PathParam("id") Long id) {

// Direct return, the runtime handles serialization

return userService.findById(id)

.map(u -> new UserResponse(u.getId(), u.getUsername(), "ACTIVE"))

.orElseThrow(() -> new NotFoundException("User not found"));

}

}This code is portable. I can run this on Open Liberty, WildFly, Payara, or even compile it natively with Quarkus. That portability is my safety net. If one vendor changes their licensing terms or stops supporting a version I need, I can move my core business logic with minimal friction.

The Virtual Thread Revolution

The most significant shift I’ve utilized this year is the integration of Java Virtual Threads (Project Loom) within the Jakarta EE container. For years, we had to rely on complex reactive programming models (like RxJava or Reactor) to handle high-concurrency scenarios. While Java Async programming is powerful, it makes debugging a nightmare. Stack traces in reactive code are practically useless.

With Jakarta EE 11 running on Java 21+, I can write blocking code that scales like non-blocking code. The container handles the thread management. I simply annotate my method or configure the executor service, and the JVM handles the suspension and resumption of virtual threads.

I recently refactored a service that was using a complex chain of CompletableFuture calls to aggregate data from three different upstream APIs. It was hard to read and harder to test. I rewrote it using standard imperative style, relying on the container’s virtual thread support. The performance remained the same, but the code complexity dropped by 60%. That is a maintainability win I will take any day.

MicroProfile: The Innovation Engine

You can’t talk about Jakarta EE without mentioning Eclipse MicroProfile. While Jakarta EE moves deliberately (which is good for standards), MicroProfile moves fast. I treat them as a single stack. I rarely write a “pure” Jakarta EE app anymore; it’s always a hybrid.

My favorite tools in this box are Config, Fault Tolerance, and Health. Before these standards, I had to write custom code to read environment variables or handle retries. Now, it’s just an annotation.

For example, in a recent Java Microservices project deployed to Kubernetes, I needed to ensure that a flaky payment gateway didn’t crash my entire order processing service. Using the MicroProfile Fault Tolerance spec, I solved this in two lines of code.

import org.eclipse.microprofile.faulttolerance.Retry;

import org.eclipse.microprofile.faulttolerance.Fallback;

import org.eclipse.microprofile.faulttolerance.Timeout;

@ApplicationScoped

public class PaymentService {

@Timeout(500) // Fail if it takes longer than 500ms

@Retry(maxRetries = 3, delay = 200)

@Fallback(fallbackMethod = "queuePaymentForLater")

public PaymentResult processPayment(Order order) {

// Call external, flaky REST API

return externalGateway.charge(order.getTotal());

}

public PaymentResult queuePaymentForLater(Order order) {

// Logic to save to DB for a background job to pick up

return PaymentResult.pending();

}

}If I tried to implement this exponential backoff and circuit breaking manually, I would introduce bugs. Relying on the standard implementation means I trust the container provider to get the threading logic right.

CDI: The Glue That Holds It All Together

Contexts and Dependency Injection (CDI) is, in my opinion, the crown jewel of the platform. It is strictly typed, contextual, and extremely powerful. I often see developers coming from Spring struggling with CDI scopes (@RequestScoped, @ApplicationScoped), but once it clicks, it provides incredibly granular control over object lifecycles.

One pattern I use extensively is CDI Events for decoupling components. Instead of Service A calling Service B directly, Service A fires an event. Service B observes it. This makes my Java Architecture much cleaner and easier to test. If I want to add a notification service later, I just add a new observer. I don’t have to touch the code in Service A.

// The Event

public record OrderCreated(String orderId, double amount) {}

// The Producer

@Stateless

public class OrderService {

@Inject

Event<OrderCreated> orderEvent;

public void checkout(Order order) {

// persistence logic...

orderEvent.fire(new OrderCreated(order.getId(), order.getAmount()));

}

}

// The Consumer

@ApplicationScoped

public class InventoryUpdater {

// This runs in the same transaction phase by default, or can be async

public void onOrder(@Observes OrderCreated event) {

System.out.println("Updating inventory for order: " + event.orderId());

}

}The Cloud Native Reality

A few years ago, the criticism was valid: Jakarta EE application servers were too heavy for Docker Java containers. They took too long to start, used too much memory, and didn’t fit the ephemeral nature of Kubernetes Java pods.

That argument is dead. Frameworks like Quarkus and Helidon have completely changed the game while still using Jakarta EE APIs. I can compile a Jakarta REST application into a native binary using GraalVM, resulting in a startup time of milliseconds and a memory footprint of a few dozen megabytes. This allows me to use the standards I know (JPA, JAX-RS, CDI) in a serverless environment like AWS Lambda or Google Cloud Run.

I recently migrated a legacy Java Web Development project from a heavy WebLogic instance to Quarkus. We didn’t have to rewrite the business logic because it was all standard JPA and EJB (mapped to CDI). We just changed the configuration, adjusted the build pipeline to use Maven properly, and suddenly we had a modern, cloud-native application. The team didn’t have to learn a new language or a proprietary framework API.

Why I Stick with Standards

There is a cost to non-standard frameworks. I have seen frameworks rise and fall. I have seen proprietary configuration formats become unsupported. I have seen “innovative” database access layers get abandoned by their maintainers.

When I write against Jakarta EE, I am writing against a specification that is owned by a foundation, not a single company. The Eclipse Foundation stewardship has been crucial here. It ensures that multiple vendors (IBM, Red Hat, Payara, Tomitribe) compete to provide the best implementation. This competition drives performance improvements. If one vendor’s implementation of Java JSON processing is slow, I can swap the library or the server without rewriting my code.

It also simplifies hiring. If I put out a job description for a “Jakarta EE Developer” or “Java Enterprise Developer,” candidates know what that means. They know JPA. They know Servlets. If I hire for a niche framework, I have to train them on that specific tool’s quirks.

Looking Ahead to 2026

As we close out 2025, my advice to fellow developers and architects is simple: Don’t sleep on the standards. The ecosystem is healthier than it has been in a decade. The tooling around Java DevOps and CI/CD for Jakarta EE apps is mature.

If you are starting a new project today, you don’t need to default to the “cool” option. Look at the requirements. If you need long-term stability, vendor neutrality, and a massive pool of talent, the “boring” choice of Jakarta EE is likely the right one. And with the modern performance of Java 21 and native compilation, “boring” has never been this fast.

I’m betting my next major project on it. Not because I’m nostalgic, but because I want my code to still be running five years from now without needing a complete rewrite.